From the Empire State Building to the Statue of Liberty, New York has always been defined by its landmarks. Today, a new generation of modern landmarks continues that legacy—innovative designs that reflect the city’s perpetual evolution and boundless ambition.

Table of Contents

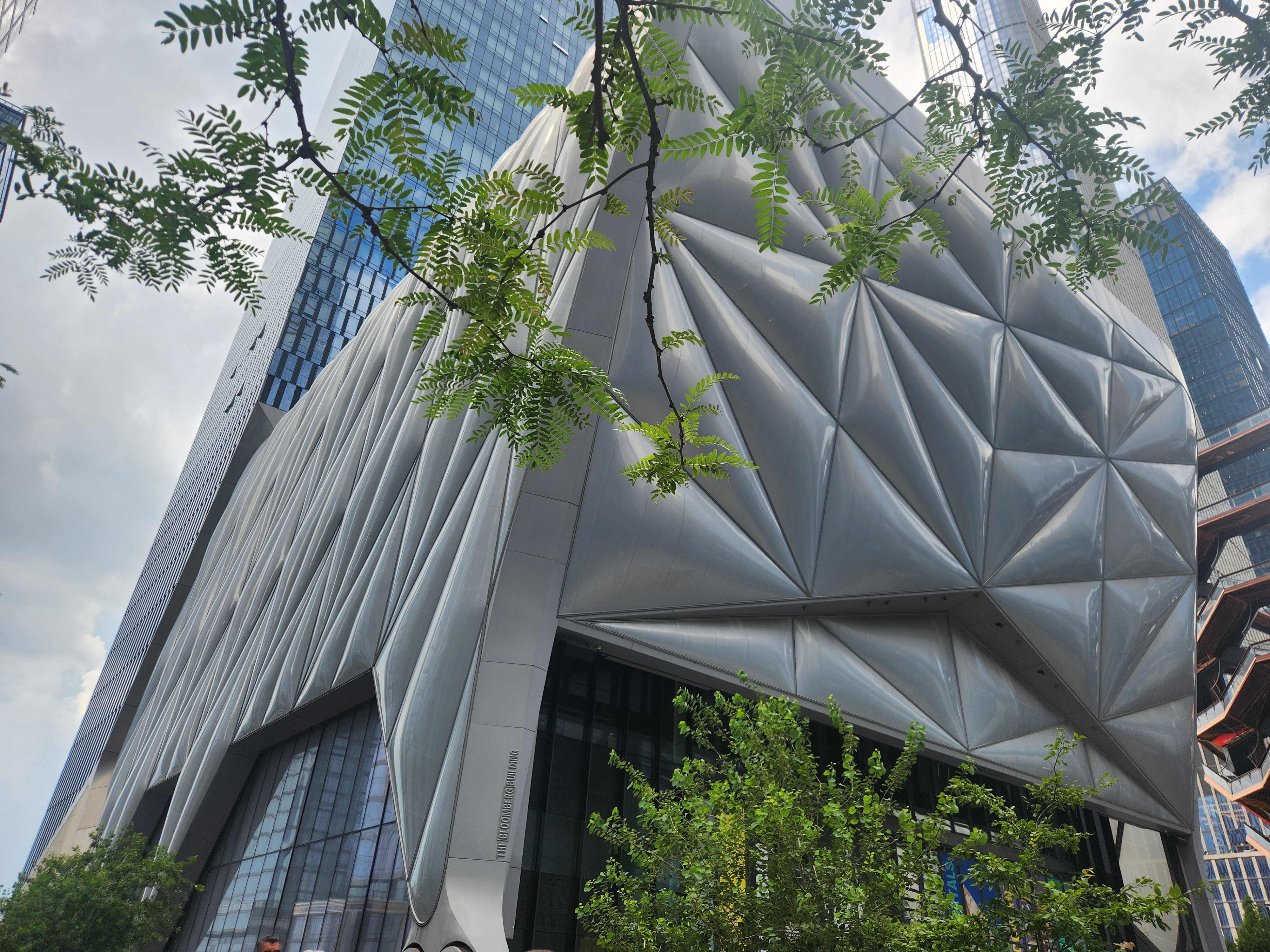

The Shed at Hudson Yards

The Shed is a cultural center unlike any other. Spanning 200,000 square feet, it is both monumental in scale and agile in design. Its most striking feature is a gigantic outer shell mounted on wheels that glide along a short track. This retractable structure, paired with the building’s eight-story base, creates The McCourt—a dramatic hall designed for large-scale performances and installations. With the push of a button, the eight-million-pound shell can roll open in just five minutes, unveiling an entirely new performance space! The McCourt can accommodate up to 1,200 guests seated or 2,700 standing, with capacity reaching 3,000 when combined with adjacent galleries.

Despite its futuristic appearance, the mechanics behind this innovation are surprisingly modest: moving the entire shell requires no more horsepower than a single Toyota Prius engine.

Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Rockwell Group, The Shed introduces a new form of a cultural center in the 21st century—not only striking, but also flexible in shape and adaptable to the task.

The Vessel at Hudson Yards

The Vessel, designed by Thomas Heatherwick, stands as the striking centerpiece of Hudson Yards—a standalone climbable sculpture. Soaring 16 stories (about 150 feet), it forms a honeycomb of 154 staircases, 2,500 steps, and 80 landings, inviting visitors to climb upward for shifting perspectives of the city and the Hudson River. Conceived as a piece of “urban furniture” rather than a conventional monument, the Vessel was inspired by ancient Indian stepwells—vast, sunken structures with long flights of stone steps leading down to water. Unlike ordinary wells, stepwells extended deep underground, with terraces, pavilions, and carved galleries that allowed access to shifting water levels. They doubled as social hubs: shaded gathering communal places.

While the concept carried a sense of history and social engagement, the price tag proved quite shocking. Initially projected at $75 million, costs nearly doubled to between $150–200 million, sparking criticism from New Yorkers who viewed it as an extravagant indulgence. The Vessel was fabricated in Monfalcone, Italy, shipped in segments across the Atlantic, and assembled on-site in 2017 before opening to the public on March 15, 2019 with much fanfare.

The opinions remain divided. Admirers celebrate its drama and the way it energizes public space; detractors dismiss it as a “stairway to nowhere”—a gleaming folly without substance. Yet, love it or loathe it, the Vessel is now a part of our skyline, reflecting New York’s ambition for bold, attention-grabbing design.

Little Island on the Hudson

Rising from 280 concrete piles, each topped with a tulip-shaped planter, Little Island seems to float above the Hudson River. Designed by Thomas Heatherwick—also the mind behind Hudson Yards’ Vessel—it is part sculpture, part park, part stage. Conceived as both landscape and performance space, Little Island blends natural shapes and unconventional architecture.

At its heart are two gathering spaces:

- The Amph – a 687-seat outdoor theater facing west, ideally placed for unforgettable sunsets, hosting concerts and shows—often free or low-cost.

- The Glade – a more intimate lawn with about 200 seats, designed for storytelling, talks, and community programming.

The idea of floating leisure spaces over the water is not new to New York. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the city’s rivers were dotted with floating bathhouses and river clubs—barges moored offshore where people swam, socialized, and escaped the summer heat. Wealthier New Yorkers enjoyed private floating clubs with dining and dancing. While Little Island isn’t a direct revival of those traditions, it echoes their spirit: a place suspended above the water, designed for both leisure and community.

Its creation was made possible almost entirely by private philanthropy. Media mogul Barry Diller and his wife, fashion designer Diane von Fürstenberg, funded nearly the entire project through their family foundation, contributing over $260 million. It is as one of the rare cases where a single family’s vision reshaped the city’s public realm.

The site itself carries deep history. Little Island rises from the footprint of Pier 54, once part of the Cunard–White Star Line. It was here that Titanic survivors were brought ashore in 1912 and where the Lusitania departed on her final voyage in 1915.

Little Island is more than a park. It is an urban floating retreat where art, architecture, and landscape meet, offering New Yorkers a stage above the river.

The Oculus — World Trade Center Transportation Hub

The centerpiece of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, the Oculus, is a dramatic architectural gesture. Its form is unmistakable: a gleaming white ribcage of steel and glass that soars upward like the wings of a bird in flight. Designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, it opened in 2016 and quickly became one of Manhattan’s most photographed landmarks.

Calatrava described the structure as a dove released from a child’s hands, symbolizing peace and rebirth at Ground Zero. The Oculus serves as a major transit hub, connecting 12 subway lines with PATH trains to New Jersey. Not just a train station, it also functions as a public space, shopping center, and memorial.

A signature feature is the skylight along its spine, called the “oculus,” which opens each year on September 11 at 10:28 a.m., the moment the North Tower collapsed, filling the interior with light as a solemn tribute.

The station’s costs skyrocketed from an initial $2 billion to nearly $4 billion, earning The Oculus the dubious distinction of the world’s most expensive train station.

With its gleaming cathedral-like interior that houses retail, dining, and open space, it joined the ranks of Manhattan’s most visited landmarks.

St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church and National Shrine

Designed by Santiago Calatrava, St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church and National Shrine is the only religious structure rebuilt at the World Trade Center site.

The original church, founded in 1916, stood on this site until it was destroyed in the collapse of World Trade Center Tower 2 on September 11, 2001. From that day forward, the guiding inspiration for its reconstruction has been the words: “Rebuild My Church.” Purchased by Greek immigrants as a community home, the original St. Nicholas was the first stop for many newcomers to New York, offering spiritual and social support immediately after disembarking from Ellis Island and glimpsing the Statue of Liberty. The church’s patron saint, Saint Nicholas of Myra, was renowned for his generosity, piety, and protection of the vulnerable—especially sailors and children. As the patron saint of sailors, merchants, and travelers, he was a fitting figure for a church along New York’s waterfront.

The rebuilt church draws heavily on Byzantine influences, inspired by Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Its dome features 40 ribs and 40 windows, echoing Hagia Sophia’s rhythm while flooding the interior with natural light. The structure is clad in thin Pentelic marble, the same historic marble used for the Parthenon. Ultra-thin stone and glass panels, backlit at night, make the building appear as if it “glows by the light of 10,000 candles,” while by day it presents a bright, solid white presence.

Today, Saint Nicholas—the only house of worship destroyed on 9/11—stands not only as a Greek Orthodox parish but also as a National Shrine and place of pilgrimage. As the only non-secular building at the WTC, it welcomes all visitors and includes a nondenominational bereavement center, offering a space for reflection, healing, and remembrance.

Look at how the new office towers are re-shaping New York’s landscape: New Office Towers Reshaping NYC’s Skyline

Leave a Reply